Parasitic insects are a broad and ecologically significant group of species that exploit other animals to complete their life cycles, often with complex behaviors and profound impacts on hosts and ecosystems. This article provides a comprehensive overview of their taxonomic diversity, life history strategies, interactions with hosts, ecological roles and implications for conservation and veterinary practice.

What are parasitic insects?

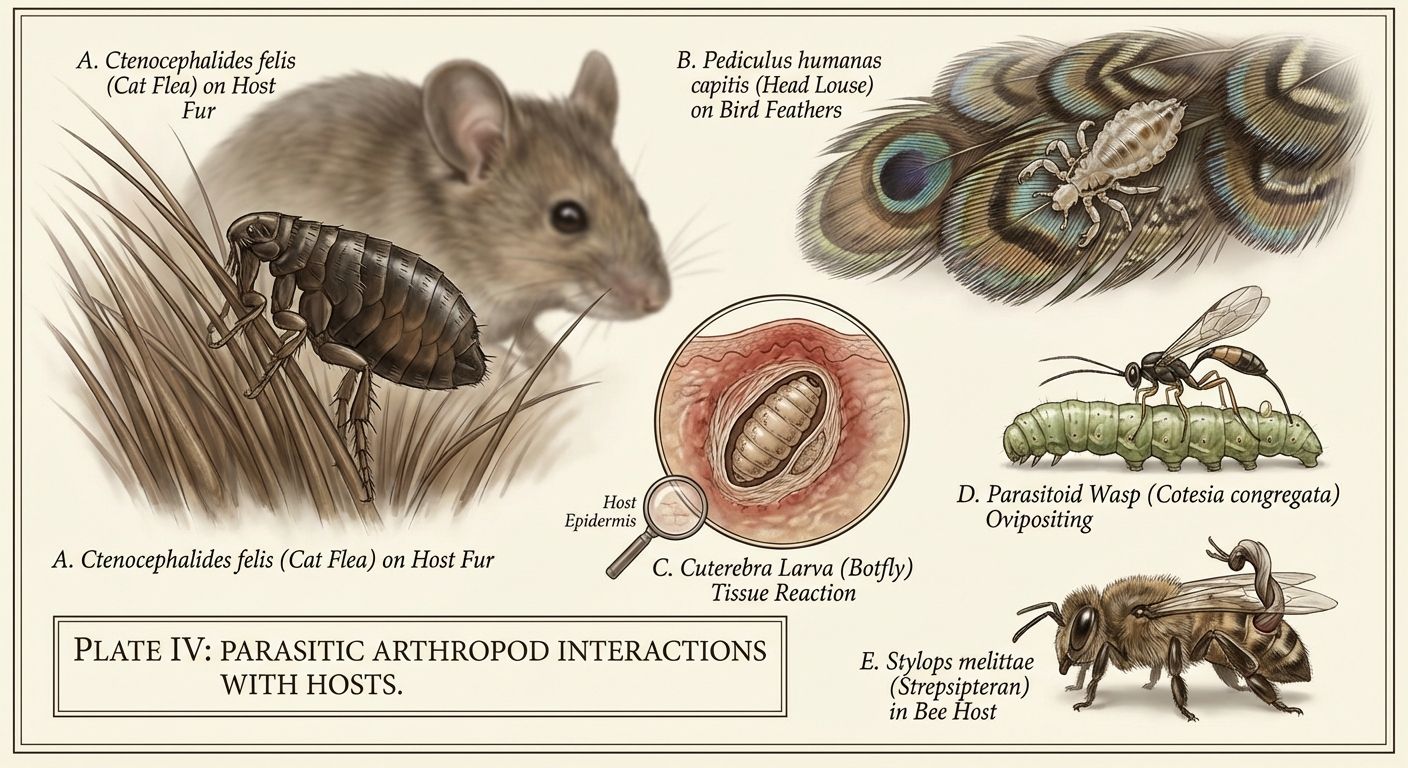

In biology, parasitism is a relationship where one organism (the parasite) benefits at the expense of another (the host). Parasitic insects include true parasites—organisms that typically do not kill their host—and parasitoids, which ultimately kill the host as part of development. Important groups include fleas (Siphonaptera), lice (Phthiraptera), botflies (Oestridae), parasitic wasps (e.g., Ichneumonidae, Braconidae), tachinid flies, and unique orders like Strepsiptera.

Key categories and representative species

Ectoparasites (external parasites)

- Fleas (e.g., Ctenocephalides felis): external blood-feeders that affect mammals and can transmit pathogens like Rickettsia or Yersinia pestis historically.

- Lice (Anoplura and Mallophaga): host-specific insects that feed on blood or skin, important in wildlife and domestic animal health.

- Parasitic flies causing myiasis (e.g., botflies like Dermatobia hominis): larvae develop in the tissues of vertebrate hosts.

Endoparasites (internal parasites)

Many insect larvae act as internal parasites. Dipteran larvae (e.g., certain blowfly larvae) can infest internal cavities; parasitic wasp larvae develop inside caterpillars or beetle larvae, consuming host tissues from within.

Parasitoids

Parasitoid wasps and some flies lay eggs on or in a host; the hatching larvae feed and eventually kill the host. Parasitoids are ecologically crucial as biological control agents against pest insects.

Specialized and unusual groups

- Strepsiptera: endoparasitic insects with remarkable sexual dimorphism; males are free-flying while females often remain embedded in host bodies (e.g., bees, wasps).

- Phoridae (some species): parasitoids of ants, sometimes decapitating hosts or manipulating behavior.

Survival strategies and life cycles

Parasitic insects have evolved diverse strategies to find hosts, avoid host defenses, and optimize offspring survival. Key strategies include:

- Host specificity vs. generalism: some species are highly host-specific while others exploit multiple host species.

- Egg placement and stealth: eggs may be glued to host hair, delivered by vectors, or laid on foliage to attach to passing hosts.

- Physiological adaptations: anticoagulant saliva in blood-feeders, cuticle resistance to host grooming, or immunosuppressive secretions by larvae.

- Behavioral manipulation: certain parasitoids alter host behavior to protect the developing parasite (e.g., inducing hosts to move to safer microhabitats).

Life cycles vary: fleas undergo complete metamorphosis (egg, larva, pupa, adult) while lice have incomplete metamorphosis (egg, nymph, adult). Parasitoid wasps may develop internally (endoparasitoids) or externally (ectoparasitoids), and many synchronize reproduction with host phenology.

Host effects: pathology and behavioral changes

Impacts on hosts range from minor irritations to severe morbidity and mortality. Typical effects include:

- Direct tissue damage from feeding larvae or blood loss.

- Secondary infections at wound sites.

- Vector-borne disease transmission, where insects transmit viruses, bacteria or protozoa (e.g., fleas and plague; some flies transmitting trypanosomes or filarial nematodes).

- Behavioral modification—reduced foraging, increased grooming, or manipulated actions that benefit the parasite.

Veterinary implications are significant: heavy infestations of fleas or lice can cause anemia in young or small animals; myiasis can lead to severe tissue destruction. Parasitoids typically target pest species and are less of a veterinary concern, but they can alter host population dynamics in wildlife.

Ecological roles and ecosystem impacts

Parasitic insects are not merely harmful agents; they are integral to ecological networks. Their roles include:

- Regulating host populations: density-dependent parasitism can control outbreaks of herbivorous insects.

- Food web contributions: parasites create trophic links and can increase biodiversity by preventing dominance by a single species.

- Biocontrol agents: many parasitoid wasps are used in agricultural pest management (e.g., Trichogramma spp.).

- Ecosystem engineering: heavy parasitism can shift community composition, indirectly affecting plant communities and nutrient cycles.

Case studies: the use of parasitoids in integrated pest management (IPM) demonstrates positive ecosystem services, while invasive parasitic insects (or their introduction without proper assessment) can destabilize native communities.

Host-parasite coevolution and adaptations

Long-term coevolution drives intricate adaptations:

- Host defenses: grooming behaviors, immune system recognition, and behavioral avoidance.

- Parasite countermeasures: rapid life cycles, antigenic variation, protective cocoons, and biochemical immune suppression.

Genetic studies increasingly reveal arms-race dynamics where both host and parasite show signatures of selection. Understanding these dynamics is important for conservation genetics, wildlife disease management and predicting responses to environmental change.

Detection, monitoring and research methods

Common methods for studying parasitic insects include:

- Field surveys: visual inspection, sticky traps, and host sampling.

- Molecular diagnostics: PCR and metabarcoding to identify cryptic species and gut contents.

- Laboratory rearing: to observe life cycles and host specificity.

- Behavioral assays: to study host manipulation and parasite attraction cues.

Refer to authoritative sources for methods: for taxonomic guidance see the Entomological Society, and for molecular approaches consult recent reviews in journals like Parasitology and Molecular Ecology.

Management, control and ethical considerations

Management depends on context. In veterinary settings, recommended steps include:

- Accurate diagnosis (identify parasitic insect species).

- Targeted treatments (topical insecticides, systemic therapies or environmental control for larvae).

- Integrated approaches combining sanitation, host health improvement and biological control when appropriate.

In conservation and agriculture, decisions must weigh benefits of parasitic insects as natural regulators against negative effects on threatened hosts. Introducing biocontrol agents requires rigorous risk assessment to avoid non-target impacts.

Practical tips for enthusiasts, students and professionals

- For students: focus on life-history diversity—compare an ectoparasite like a flea to an endoparasitoid wasp to understand contrasting strategies.

- For researchers: use integrative taxonomy (morphology + genetics) to resolve cryptic complexes.

- For wildlife enthusiasts: practice ethical observation—do not disturb hosts to collect parasites, report findings to local biodiversity initiatives instead.

- For veterinarians: include parasite surveillance in herd/flock health plans and educate owners about environmental stages of parasites.

Further reading and resources

- Entomological Society resources: entomology.org

- FAO guidance on integrated pest management: fao.org

- Peer-reviewed literature: check Journal of Insect Physiology, Parasitology and Biological Control for recent studies.

Conclusion

Parasitic insects are diverse, ecologically influential and scientifically fascinating. They illustrate complex evolutionary strategies—from stealthy ectoparasites to lethal parasitoids—and play essential roles in regulating populations and shaping ecosystems. Understanding their biology benefits wildlife conservation, veterinary medicine and sustainable agriculture.

If you are studying or managing parasitic insects, prioritize accurate identification, consider ecological context, and consult primary literature and experts when planning interventions.