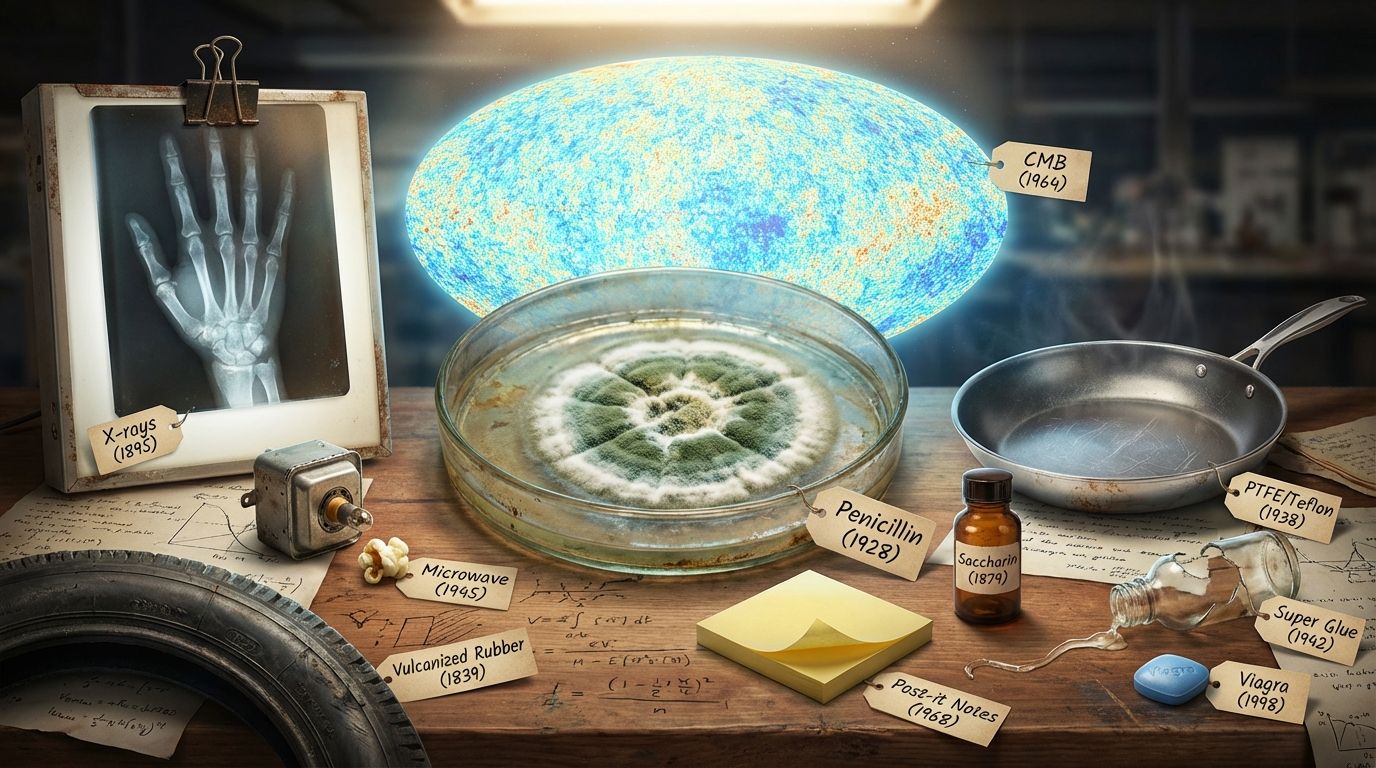

Discoveries made by accident have produced some of the most consequential breakthroughs in medicine, materials science and our understanding of the universe. This list highlights ten seminal serendipitous findings, explaining the context in which they occurred, the people involved and the lasting scientific and social impacts.

Why accidental discoveries matter

Not every major advance in science begins with a clear hypothesis. Many pivotal innovations arise when researchers notice an unexpected result and follow it with curiosity, rigor and reproducible experiments. These accidental discoveries—also known as serendipitous findings—illustrate how observation, open-mindedness and careful documentation can transform an error into a revolution.

How this list was selected

The selections below prioritize discoveries with broad scientific or societal impact, clear historical documentation, and instructive narratives that help students and teachers extract lessons about the scientific method and innovation. Where useful, external sources are provided for further reading.

1. Penicillin — Alexander Fleming (1928)

Context: In September 1928, Scottish bacteriologist Alexander Fleming returned from holiday to find that a Petri dish of Staphylococcus bacteria had been contaminated by a mold (Penicillium notatum) that killed the surrounding bacteria.

What happened: Fleming noticed a clear zone around mold colonies and deduced that the mold produced a substance that inhibited bacterial growth. He named it penicillin and published his observations, but it took a decade of development by Howard Florey, Ernst Chain and others to produce usable drugs for mass treatment.

Impact: Penicillin launched the antibiotic era and has saved millions of lives. It transformed surgery, military medicine and public health, and it stimulated intense research into antimicrobial agents. See Britannica for more on Fleming: Britannica – Alexander Fleming.

Key lessons

- Careful observation matters: Fleming’s notebook notes preserved the path from contamination to discovery.

- Serendipity plus follow-up work is required: isolation, purification and clinical testing made penicillin practical.

2. X-rays — Wilhelm Röntgen (1895)

Context: While experimenting with cathode rays in late 1895, German physicist Wilhelm Röntgen noticed that a fluorescent screen across the room glowed even though it was shielded. He realized a new kind of penetrating radiation was being emitted from his vacuum tube.

What happened: Röntgen produced the first X-ray image—the hand of his wife, showing bones and her wedding ring. He named the phenomenon “X” rays and published his findings, quickly spurring medical adoption.

Impact: X-rays revolutionized diagnostics, surgery and materials inspection. They inaugurated radiology as a medical specialty and had immediate practical uses in industry and science. Read more: Britannica – X-ray.

Key lessons

- Unexpected experimental results can point to entirely new physical phenomena.

- Immediate practical use accelerated acceptance—doctors quickly adopted X-rays for diagnosing fractures and foreign objects.

3. Microwave oven — Percy Spencer (1945)

Context: While testing magnetrons for radar equipment during World War II, engineer Percy Spencer noticed a candy bar melted in his pocket. He investigated and realized microwaves could heat food quickly.

What happened: Spencer experimented with popcorn and eggs and built prototype microwave cooking devices. Raytheon commercialized the first microwave ovens in the late 1940s and 1950s.

Impact: The microwave oven transformed domestic food preparation and food industry processes, enabling rapid reheating, defrosting and microwave-specific cooking techniques.

More on Percy Spencer and microwave history: Britannica – Percy Spencer.

4. Vulcanized rubber — Charles Goodyear (1839)

Context: Charles Goodyear had been experimenting with natural rubber, which was sticky and deformed in heat and brittle in cold. According to popular accounts, he accidentally dropped a mixture of rubber and sulfur on a hot stove, producing a more durable substance.

What happened: The resulting material—vulcanized rubber—retained elasticity over a wider temperature range and resisted wear. Goodyear patented the process and it became central to tires, industrial belts, hoses and many rubber goods.

Impact: Vulcanization enabled the growth of the automotive industry and countless rubber-based technologies. It is a foundational innovation in modern manufacturing.

5. Teflon — Roy J. Plunkett (1938)

Context: While experimenting with gases related to refrigerants at DuPont, chemist Roy Plunkett found a cylinder of tetrafluoroethylene that had polymerized into a white, waxy solid.

What happened: Plunkett and colleagues investigated the unusual polymer, polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE), later marketed as Teflon. PTFE has extremely low friction and chemical inertness.

Impact: Teflon became invaluable for non-stick cookware, chemical processing equipment, and applications requiring low-friction, corrosion-resistant surfaces. For more, see DuPont history and chemical descriptions: Chemistry World (search “Teflon”).

6. Post-it Notes — Spencer Silver & Art Fry (1970s)

Context: Spencer Silver, a researcher at 3M, developed a low-tack adhesive that stuck lightly but could be repositioned—initially seen as a failed strong adhesive. Art Fry, a colleague frustrated by bookmarks falling out of his hymnal, realized Silver’s adhesive could solve his problem.

What happened: The pair developed repositionable notes that became known as Post-it Notes. 3M eventually launched them commercially in the late 1970s and early 1980s.

Impact: Post-it Notes changed office organization, brainstorming practices and personal reminders, becoming a ubiquitous cultural and productivity tool.

7. Saccharin — Constantin Fahlberg (1879)

Context: Working with coal tar derivatives in Ira Remsen’s laboratory at Johns Hopkins, chemist Constantin Fahlberg went home for dinner and noticed his bread tasted unusually sweet. He traced the sweetness back to compounds on his hands from lab work and isolated the artificial sweetener saccharin.

What happened: Saccharin was commercialized as a calorie-free sweetener and used widely in food and beverages, especially during sugar shortages and for people managing diabetes.

Impact: Saccharin’s discovery ushered in the era of artificial sweeteners and influenced food industry formulations. It also initiated decades of study into long-term safety and regulatory review for additives and substitutes.

8. Super Glue (cyanoacrylate) — Harry Coover (1942; commercialized 1950s)

Context: While searching for clear plastics for gun sights during World War II, chemist Harry Coover found a fast-bonding adhesive that stuck to everything and was initially dismissed as a nuisance. Later, the adhesive’s properties were recognized and refined.

What happened: Cyanoacrylate adhesives (commonly called Super Glue) were commercialized in the 1950s. Their extremely fast bonding and versatility made them ideal for household, industrial and medical uses (including some surgical adhesives).

Impact: Super Glue became a staple in repair kits, manufacturing and specialized applications where quick adhesion is required.

9. Viagra (sildenafil) — Pfizer (1998)

Context: Sildenafil was initially developed at Pfizer to treat hypertension and angina. During clinical trials, a common side effect—improved erectile function—appeared repeatedly.

What happened: Researchers recognized the drug’s effectiveness for erectile dysfunction and redirected development and marketing. Viagra was approved in 1998 and became one of the fastest-selling pharmaceuticals in history.

Impact: Viagra transformed treatment for erectile dysfunction and spurred research into the biochemical pathways involved (notably nitric oxide and phosphodiesterase inhibition). It also had social and cultural effects related to sexual health and pharmaceutical marketing.

10. Cosmic Microwave Background Radiation — Arno Penzias & Robert Wilson (1964)

Context: Radio astronomers Arno Penzias and Robert Wilson were calibrating a horn antenna at Bell Labs and encountered persistent microwave noise that could not be traced to instrumental or environmental sources (including pigeon droppings).

What happened: After ruling out local causes, they learned of theoretical predictions for relic radiation from the Big Bang. Their observation provided strong empirical support for the Big Bang model of cosmology and earned them the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1978.

Impact: The discovery of the cosmic microwave background (CMB) fundamentally shaped cosmology, providing a snapshot of the early universe and enabling precision measurements of cosmic parameters. See NASA/COBE and Nobel documentation: NASA – CMB and COBE.

Common threads and lessons from serendipitous discoveries

- Observation and curiosity: Many discoveries started with an unexpected observation—followed by careful inquiry.

- Documentation: Good lab notes and reproducible experiments turned anomalies into accepted science.

- Interdisciplinary thinking: Accidental findings often cross fields: chemistry, biology, physics and engineering converged in many cases.

- From failure to value: Materials or results initially labeled as “failed” sometimes became valuable inventions.

How to teach or present these stories

For students and teachers, these stories are powerful examples of the scientific mindset. Suggested classroom activities:

- Case-study discussions comparing the initial observation and the subsequent validation steps.

- Role-play: students act as the original researchers and defend why they followed an unexpected lead.

- Research assignments linking each discovery to modern applications (e.g., antibiotics today, non-stick materials, or cosmology missions).

For content creators, present these narratives visually: timelines, before-and-after illustrations, and short explainer videos that emphasize the human and procedural elements of discovery.

Further reading and sources

- Britannica biographies and topic pages for detailed historical context (e.g., Fleming, Röntgen, Percy Spencer).

- Nobel Prize archives for award-winning follow-up work (e.g., Penzias & Wilson).

- Primary literature and historical reviews for each topic—search academic databases (PubMed, JSTOR) for authoritative sources.

Conclusion

Stories of discoveries made by accident remind us that science is not only planned experiments and sterile hypotheses—it’s also an endeavor propelled by attention to the unexpected. From lifesaving antibiotics and diagnostic X-rays to everyday conveniences like Teflon and Post-it Notes, serendipity combined with rigorous follow-up has repeatedly reshaped the world. Encourage curiosity, keep careful records, and remain open: the next accidental discovery might be in your lab or workshop.

If you’re a teacher or content creator, consider using these ten cases as springboards for lessons on the scientific method, ethics in innovation and the process that turns observation into invention.